Pensioners and children are the groups most affected by mould in England’s private rented sector, according to the latest government data.

The English Housing Survey (EHS) revealed last year that 14% of privately rented households with children under six years old had ‘serious’ mould, while 13% of tenants over 75 faced the same issue.

Until the Renters’ Rights Bill is passed next year, tenants in the private sector remain unprotected by law when it comes to reporting and repairing serious cases of mould, and face another winter of worsening living conditions.

London Renters Union press officer Jae Vail said: “We’re paying more and more each year, yet we’re not seeing any of that money invested into the actual conditions of these properties.

“A lot of people are saying that their children are having health issues worsened by mould.

“They’re saying it has interfered with their child’s ability to study, and has a huge impact on mental health as well.”

These statistics mirror the experience of Damp and Mould Solutions founder Micken Patel, 44, who recalled a visit to a family of seven – including a pregnant mother – whose bathroom, lounge and two bedrooms were covered, wall-to-ceiling, in pitch black mould.

He said: “You’d think that someone’s painted it on, that’s how bad it was.

“The future of the world is suffering right now with no one facing consequences.”

Mould can cause respiratory illnesses for all ages but infants, young children and the elderly are most at risk due to developing or vulnerable immune systems.

Asthma + Lung UK head of advice Erika Radford said: “Mould is a major trigger for those with asthma or Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD).

“It can be very harmful, especially for babies, small children and older people, because it produces spores, which can be breathed in, causing health problems in those who are sensitive to them.”

This survey was commissioned following the inquest into the death of Awaab Ishak which ruled the two-year-old had died as a direct result of exposure to black mould in the family’s social rented property.

The hearing raised the awareness of mould as a life-or-death issue and prompted the government to gather information and draft Awaab’s Law, as part of the Social Housing (Regulation) Act 2023, to avoid any further tragedies.

The law set out to tighten restrictions on housing providers to investigate, record and start repairing serious cases of mould within a certain timeframe.

The Renter’s Rights Bill, if passed, will extend these protections to tenants in the private sector.

Scepticism remains, however, that this law, based on the findings of the English Housing Survey, will meaningfully tackle the issue.

The survey is widely believed to understate the issue of mould around the country, with alternative data gathered by Opinium finding nearly a third (29%) of the UK population experiences mould in their homes either frequently or occasionally.

Similarly, government data tells us 3.7% of London properties have damp and mould present, while Opinium suggests the number is as high as 32%.

Campaigning group Fuel Poverty Action have questioned the gulf between these statistics.

Policy and parliament lead Jonathan Bean said: “This is the problem with government.

“You end up with people who are just relying on misleading government reports and misleading data to minimise the issue and therefore any legislation doesn’t really attack the reality.”

The difference in these datasets is partly explained by the government’s use of a “category one” system, deciding which households have ‘significant enough mould to be taken into consideration’.

The survey states: “Minor issues of damp are not recorded and, for consistency, would not be part of the modelled data.”

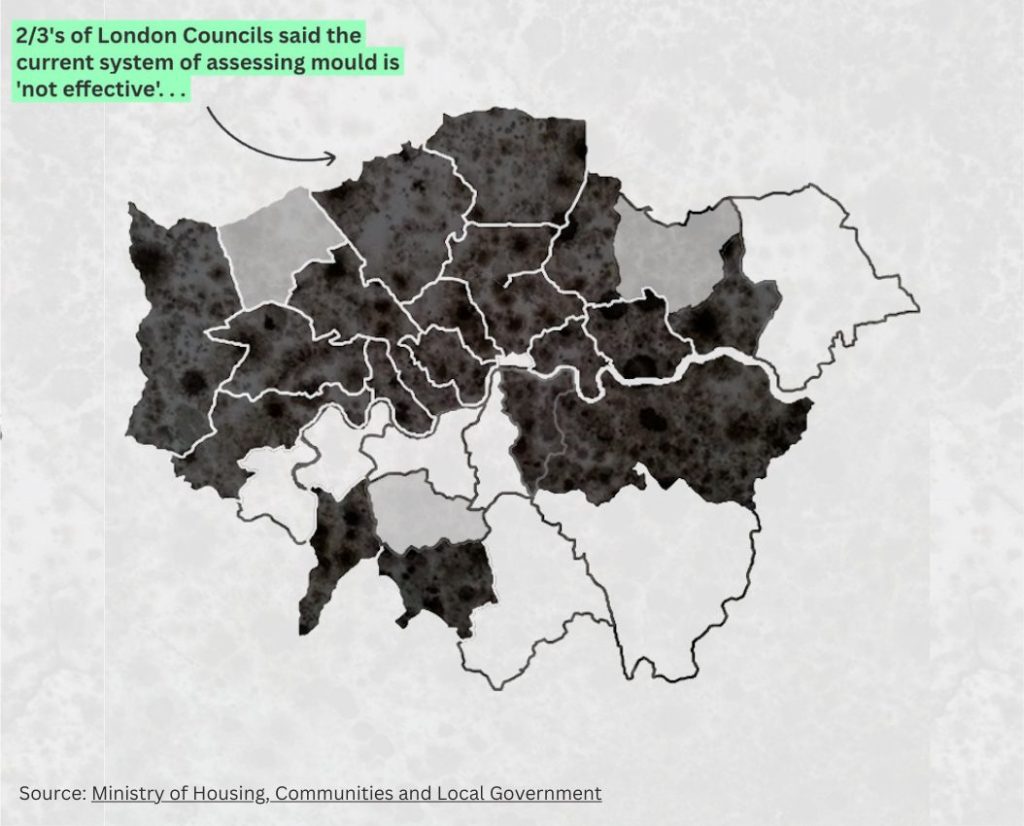

This decision was criticised by campaigners but also left London councils, who contributed to the survey, questioning the entire process.

Two-thirds of London boroughs, including Lewisham, Southwark and Greenwich, said the Housing Health and Safety Rating System (HHSRS) was not an effective way of assessing the seriousness of mould in people’s homes.

Another three boroughs said they were ‘not sure’, meaning only eight local councils had faith in the system.

But even those that successfully report a “category one” mould hazard face issues with mobilising their council into enforcement.

Jae Vail said: “People feel worried about reporting issues, because they fear they’ll be threatened with an eviction notice or hit with a big rent hike.

“So they just say, ‘okay, fine, I’ll patch up that ceiling’.”

He added that some of the union’s members have been waiting for years for their council to serve improvement notices while other complaints have been roundly ignored.

Privately rented homes with significant levels of mould, under the Renters’ Rights Bill, will be protected by various “enforcement mechanisms”, including Enforcement Actions, Improvement Notices, Civil Penalty Notices and Prosecution.

But these systems have so far proved impractical.

Between 2019 and 2022, Enfield Council received 355 mould-related complaints, but carried out only 32 inspections and served five Improvement Notices.

Lack of ‘necessary resources and appropriately trained staff’ were given as reasons why.

Hounslow Council, on the other hand, inspected all 54 of the complaints they received, serving 11 Improvement Notices.

Vail said: “It’s a complete postcode lottery.

“In addition to councils having the resources to enforce housing safety, it’s also having the political will.”

The Renters’ Rights Bill is expected to become law in the spring.

An Asthma + Lung UK spokesperson said: “If you live in rented accommodation, report any damp and mould issues to your landlord, as they have a responsibility to keep your home in good condition.

“If you would like to receive tailored advice about how to look after your lung condition over winter, please visit: www.asthmaandlung.org.uk/notjustaseason.”

Featured image credit: Alexander Davronov via Wikimedia Commons under CC BY-SA 4.0 licence

Join the discussion