The recent surge in measles cases in London has prompted innovative strategies to enhance vaccination uptake and curb the spread.

Despite a declaration from the World Health Organisation (WHO) that the disease had been eradicated in Britain seven years ago, the country now faces a measles emergency.

The UK Health Security Agency has declared a national incident signalling the growing public health risk, with the latest figures showing London remains the country’s second major hotspot.

As of March 1, the total number of measles cases confirmed since October last year is now 650 – nearly twice the total for the whole of 2023.

15% (95 of 650) of cases have been found in London, second only to the West Midlands with 63% (410 of 650).

The majority of these nationawide cases were found among children under 10.

Measles begins with cold-like symptoms that usually develop about 10 days after exposure to an infected person, and lasts seven to 10 days.

Symptoms include high fever; runny nose; red, sore, watery eyes; coughing; small red spots with bluish-white centres inside the mouth known as koplik spots, and a blotchy rash appears after several days.

The NHS website notes that the rash looks brown or red on white skin but may be harder to see on brown and black skin.

The MMR vaccine is given to children in the UK to protect against measles, mumps and rubella as part of the routine NHS vaccination schedule, first at age 1 and then again at 3 years and 4 months.

It is judged to be 99% effective over the two doses.

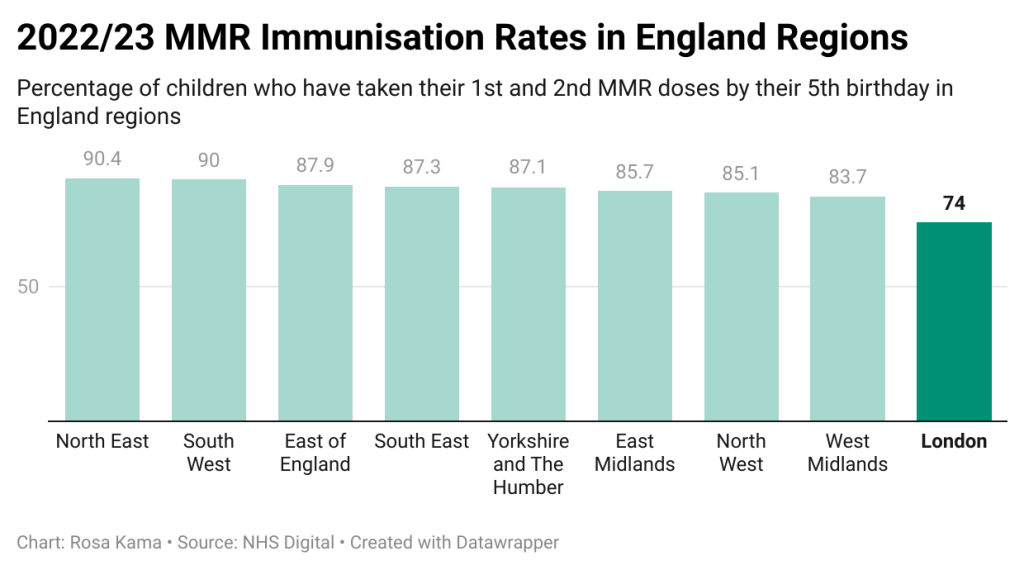

Yet in spite of the availability and effectiveness of the vaccine, vaccination rates i.e. the proportion of children who have had their first and second MMR doses, have dropped to approximately 85% nationally, the lowest level since 2010-11.

The WHO considers 95% the necessary threshold to maintain herd immunity and protect those who are not able to be vaccinated such as babies under a year old.

London has significantly lower rates of routine childhood vaccinations than other regions according to NHS data from 2022-23, with only 74% of children having received their full schedule of MMR by the age of 5.

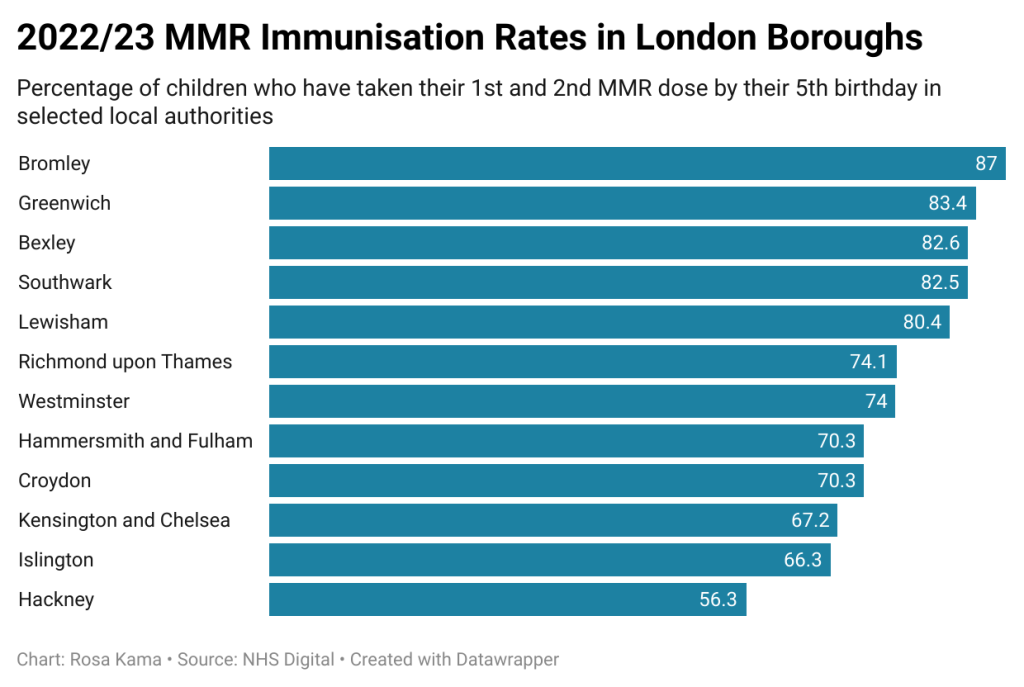

Lewisham is south east London’s lowest uptake area, whilst vaccination rates in Bexley, Greenwich and Southwark also fall below the national average.

Worst affected is Hackney, east London, where nearly half of children have not been fully vaccinated against it – the lowest proportion of any local authority in the country.

Dr Angela Bhan, Bromley Place Executive Director and Consultant in Public Health, cited mobility reasons as a cause of the fall in the uptake of vaccinations: “In London, particularly inner city areas, you sometimes have a greater mobility of the population so they may not remain in one place.

“Records get transferred from GP to GP, and parents then forget about getting the second dose even if they’ve had the first dose.”

Another factor for declining immunisation rates is misinformation about vaccines.

One of the most influential pieces of misinformation was a late 1990s study by Andrew Wakefield linking the MMR jab to autism which has long since been discredited but remains in public memory.

It is thought to have left a generation of young people born between 1998 and 2004 – the so-called ‘Wakefield cohort’ – most susceptible to missing out on vaccinations.

Cultural considerations may also be vital in understanding the trend.

This can often relate to the use of porcine gelatine in the MMR vaccine.

Dr Bhan explained: “Some faith groups might be wary about the possibility that there’s pork extract in the vaccine, but actually, we’ve got a pork-free vaccine that people can have.

“They just have to ask and make these things known to us, so it’s working with communities to try and improve uptake.

“We saw this during the COVID vaccination programs and we’re trying to use the learning from that, to talk to people, community leaders, to make sure that we can continue to engage with them about the value and the benefit of vaccination.”

Ancillary to this is the need to combat the often mistaken belief that measles is a mild childhood illness and instead emphasise that it is a highly contagious disease that can lead to serious and potentially life-threatening complications with 20% of cases requiring hospitalisation.

Children younger than 5 and adults older than 20 are more likely to suffer from complications, according to US public health agency, the CDC.

In an effort to change the trajectory of this measles outbreak, on March 4 the UKHSA spearheaded a nationwide childhood immunisations marketing campaign to remind parents and carers of the risk of their children missing out on protection with an urgent call to action to catch up on missed vaccinations.

Professor Dame Jenny Harries, Chief Executive of UKHSA, said in the press release: “We need an urgent reversal of the decline in the uptake of childhood vaccinations to protect our communities.

“Through this campaign, we particularly appeal to parents to check their children’s vaccination status and book appointments if their children have missed any immunisations.

“The ongoing measles outbreak we are seeing is a reminder of the very present threat.

“Unless uptake improves, we will start to see the diseases vaccines protect against re-emerging and causing more serious illness.”

Across the capital, health authorities have turned to pop-up clinics as a strategic intervention. These temporary vaccination centres offer a convenient and accessible way for residents to receive MMR vaccines promptly.

In Southwark, for instance, the council’s library service and public health teams, South East London NHS Integrated Care Board, and Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Trust, have arranged community catch-up clinics at libraries and community centres.

Councillor Evelyn Akoto, Southwark Cabinet Member for Health and Wellbeing, said: “A key driver of vaccine uptake is convenience.

“Offering vaccines in non-traditional venues can be more convenient, particularly for busy parents, than having to book a GP appointment.

“Some people may also feel more comfortable getting vaccinated in a community venue rather than a medical one.

“People who are not registered with a GP or without ID can also access pop-up vaccination clinics, so they have the potential to reduce health inequalities experienced by marginalised communities locally.”

Leveraging innovative strategies and community engagement initiatives will be vital as London and the rest of the UK navigates this public health crisis.

Join the discussion