“Sometimes I wonder if there is something wrong with me,” chuckles David.

He has spent the last hour discussing his passion for travel which has taken him across the world.

What could be wrong with that?

Whilst many of us may like to escape to the beach or go on cruises when we holiday, David Robinson’s destinations of choice are slightly different, taking him far from his home in Surrey.

His previous travels include: the Killing Fields in Cambodia; Auschwitz concentration camp; and the military base in Bucharest where dictator Nicolae Ceaușescu was executed.

The 58-year-old IT director is a self-proclaimed dark tourist; someone who travels to places that many people might deem taboo, extreme or distasteful.

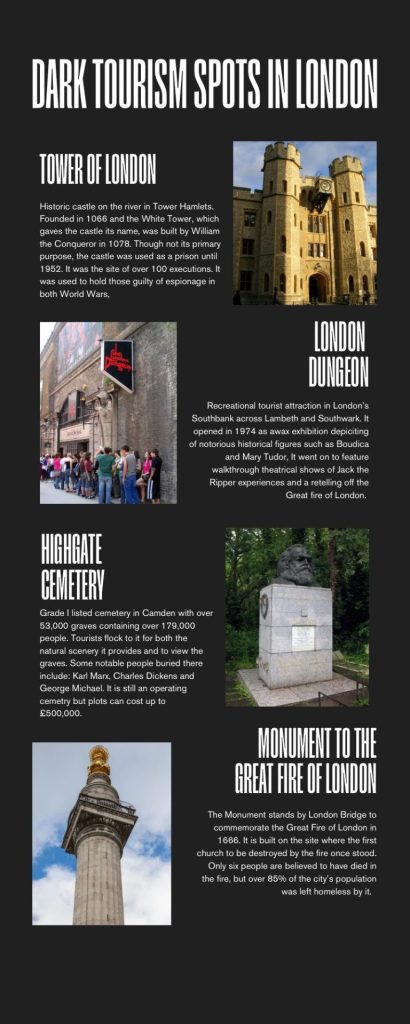

While David’s travels have taken him all across the world, you do not have to stray far from home to find dark tourism.

London, a global financial capital with a history entrenched with obscene discrepancy between the haves and have-nots, is full of sinister and murky corners of history.

Some dark tourist sites are quite obscure but still regularly attract dark tourists.

For example: the flat where Jimi Hendrix died; the site of the Dennis Nilsen murders; or the scene of the Balcombe Street siege.

These are all seemingly inconspicuous locations to the unknowing eye, but to a dark tourist they take on an entirely different significance.

However, dark tourism is much more prevalent than we may initially think.

Many of London’s most famous tourist attractions are unavoidably dark by their very nature.

The Tower of London acted as a prison and held executions which absolutely factor into tourists’ interest in it.

Jack the Ripper Walks concentrate on England’s most notorious serial-killer.

The London Dungeon replicates gruesome and morbid historical events for our amusement.

Mark Cartwright via World History Encyclopaedia. License found here

Ruth Hartnup via Flickr. License found here

Phillip Perry via Wikimedia Commons. License found here

Diego Delso via Wikimedia Commons. License found here

Initially, the phenomenon of dark tourism may seem isolated from everyday life.

But in reality, it is a convoluted and intricate topic that explores the fabrication of the world we live in, as well as the human psyche.

History that hurts: What makes a place dark?

The term “dark tourism” was coined in 1996 by Scottish academics J. John Lennon and Malcolm Foley.

The paper in which they introduced the topic had the tagline: “Attraction to Death and Disaster.”

James Treadwell is a Professor in Criminology at Staffordshire University, and co-author of 50 Dark Destinations: Crime and Contemporary Tourism.

He defines dark tourism as: “Travel to, and engagement with settings that have a history of violence, death, disaster and atrocity.”

Although the dark tourism sites mentioned have histories of darkness and violence, the definition allows for more contemporary destinations too.

Professor Treadwell gestures to a more recent account of a young British student travelling to Kabul when it became clear that the Taliban were going to take over the city in 2021.

He said: “Some people will deliberately go and take photos of themselves in danger zones because they see it as breaking barriers.

“Some people will intentionally go off the map for dark tourism.”

Filmmaker David Farrier’s Netflix documentary Dark Tourist highlights the divide between “official” dark tourist spots and the more “unofficial” off-the-map ones.

In the former category he visits a museum in Gloucestershire dedicated to so-called controversial history, and a walking tour following the life and crimes of serial-killer Jeffrey Dahmer in Milwaukee.

In the latter camp, Farrier goes to Turkmenistan to observe the present-day dictatorship, and partakes in intense voodoo rituals in Benin.

Therefore, the parameters of defining a place as dark must allow for: both the historical and the contemporary; and a dichotomy between official designated tourist experiences, and those that are not advertised as such but still draw in interest.

“Weirdos like me:” Why are people dark tourists?

People are attracted to dark tourism for different reasons.

For David, it is his love of 20th century history that drives him to his destinations of choice.

He said: “I just like to be at places where notable historical events have happened.”

By way of example, he recounts his most recent trip to Romania to visit the site of Ceaușescu’s execution.

He describes standing in the room where the dictator was killed whilst watching a YouTube video about it.

He said: “It was very eerie to be standing exactly where history happened, and the only difference is to be removed by 30 or so years.”

But David also acknowledges that his love for this particular type of travel is tied up with a fascination with man’s capacity for inhumanity.

“There is probably something in me that is wired wrong” he laughed.

However, this is almost certainly not the case.

There is a reason why true crime podcasts dominate the charts.

There is a reason why TV shows about murder and crime are so popular.

Most people, whether or not they outwardly admit it, have an interest in the dark and the morbid.

Frivolity

The danger with dark tourism is that people use it to sensationalise, glorify and even sanitise atrocities.

Places like Auschwitz have been in the news more than once, following groups of people taking selfies and posing disrespectfully at these historical sites.

David qualifies that he sees dark tourism as a serious topic and hates how some people view it as a frivolous activity.

He recounted his visit to the Czech Republic to see some historical gallows.

But when he arrived there, he found groups of people pretending to be hung and taking pictures of themselves doing so.

He said: “This isn’t a theme park.

“It’s a real place where people were killed.”

YouTuber Logan Paul made headlines in 2017 and 2018 when he filmed a video for his channel in Aokighara, Japan, often referred to as the ‘suicide forest’, due to its notoriety as a suicide site.

In the now deleted video, he included the body of a man who had recently hanged himself and then went on to make jokes about the situation.

Within 24 hours, the video gained over 6 million views.

He took it down soon after and issued an apology about the filming and his insensitivity regarding the heavy topic.

Professor Treadwell agrees that there is a tendency for people to glorify and sanitise the serious and sinister histories of some destinations.

He said: “We should be honest and overt about the range of reasons that people engage with dark tourism.

“But there can be an over sway towards the emotional aspect of why people are engaged.

“So the reasons people are dark tourists are as multi-faceted and varied as are people.”

Despite our own best protests, human beings are attracted to the morbid and nasty side of human nature.

While we may not realise it, so much of our pop culture and entertainment relies on a darker aspect.

Reality shows such as Survivor or Banged Up rely on the unquestioning engagement of bleak and dark situations.

Some people go to bars where people are made to dress in orange jumpsuits and pretend they are prisoners.

We don’t question the reality of the experience we are presented with.

People do not recognise the dark implications as the nasty side has been blended out almost.

But there is an unquestioning engagement that means people, despite thinking dark tourism as a concept is taboo, will still enjoy activities based on the morbid and criminal.

Complicity and inescapability

There are sure to be many people who still look at dark tourists with disdain and think ‘who could possibly visit those places?’

Well, the answer is everyone one of us, and not least those of us who live in London.

With the shadow of the British Empire, our nation’s history is rampant with oppression, atrocity and slavery.

London by extension then, is a city built on dark history.

Professor Treadwell suggests that most places we visit in the capital, will be haunted by the vestiges of our bitter past.

The antique chairs we like in our local restaurant; or the paintings hanging in our favourite museums are more likely than not results of dark history.

It’s why he and his co-authors included Hyde Park as one of their dark destinations in their book.

Even if you think giving attention to dark tourism is distasteful, it is impossible to not engage with it.

Professor Treadwell notes that consumerism has transformed mundane activities into passive forms of dark tourism.

London’s Monopoly Lifesize attraction has taken a game based on capitalism and greed and turned it into something more palatable.

But that does not remove its dark origins.

Likewise, something as innocent as toys can be perceived as dark, when looked at through the right lens.

Take Lego as an example.

The plastic pieces are unsustainable by their very material.

Then take into account the air pollution caused through their distribution, and the working conditions and treatment of labourers.

Regarding the above labour allegations, a spokesperson for Lego told the Guardian that ensuring respect for workers’ rights was very important.

But they also added: “In this case the code may have been broken and we are addressing this urgently.”

Professor Treadwell does admit that looking at companies and manufacturers is a very academic take.

In the age of globalisation it is impossible to take into consideration the roots and nuances of everything we consume.

But he maintains that it is the job of an academic to ask these questions.

He said: “Making these connections makes us start to think of tourism connected to darkness in different ways.

“Not all kinds of crimes are obvious or visible, and that might make us uncomfortable.

“But once you start looking for dark tourism, you will find it everywhere.”

Featured image credit: Carlos Delgado via Wikimedia Commons: Carlos Delgado; CC-BY-SA

Join the discussion