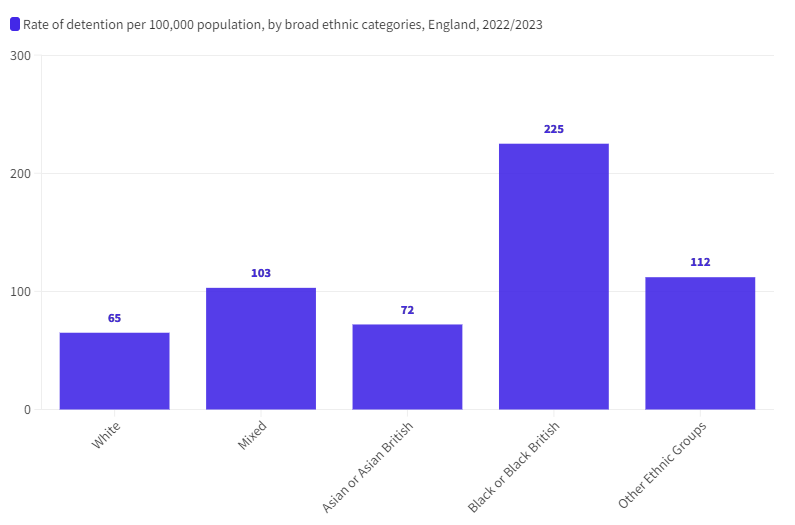

Black people in the UK are nearly four times more likely than White people to be sectioned under the Mental Health Act 1983, according to new figures released by NHS England.

They were also three times more likely to be detained than Asian/Asian British people and twice as likely as any other ethnic group.

The 2022/23 data follows a consistent trend since the figures were first published by NHS England for the year 2016/2017.

Sources: MHSDS, ECDS 2022-23 – NHS England

Research has highlighted some of the most common reasons why people from the Black community can have negative experiences of the mental health system compared to the rest of the population.

It is well documented that Black women are more likely to experience a common mental illness such as anxiety disorder or depression, and Black men are more likely to experience psychosis.

Despite these facts, Black people are receiving mental health treatment in lower numbers than White people and they are experiencing poorer outcomes as a result.

Information published by the organisation ‘Rethink Mental Illness’, highlighted the key barriers faced by the Black community when accessing mental health care services:

- Cultural barriers where mental health issues are not recognised or seen as being important.

- Medical professionals having a lack of knowledge about things which are important to someone from a Black background, or their lived experiences.

- White healthcare professionals not being able to fully understand what racism or discrimination is like.

- Stereotyping which can take the form of medical professionals thinking that Black people with mental health issues will get angry and aggressive.

- Unconscious or conscious biases by medical professionals when it comes to the way they view mental health in some communities.

- Stigma about mental health within the community, this may cause people to feel ashamed and not seek help.

Vivienne Williams, a nurse, social worker, and trainer, has conducted mental health workshops with the Croydon BME Forum, focusing on disproportionality and the safeguarding of black boys.

VIVIENNE WILLIAMS – Photo Credit: Vivienne Williams

Williams said: “Black people are treated differently when we break.

“Our children are given a kind of punitive approach to mental health issues.

“We knew this from the 1980s, where we saw our children being over prescribed as well as over sectioned.

“When social ills are prevalent within a society, those who are disadvantaged to begin with feel it worse.”

Inequalities in wealth and living standards are also listed as contributing factors in the high rates of mental illness for Black people and people from other ethnic minorities.

Emma Turner, CEO of mental health charity Mind in Croydon, has worked at the organisation for 13 years.

Turner started her career as a front line independent mental health support worker, a volunteer ‘befriender’ in Lewisham, who would visit people in their homes to offer support.

EMMA TURNER – Photo Credit: Mind in Croydon

Recounting her experiences of working within Wormwood Scrubs Prison, she encountered young Black men who were subject to the Mental Health Act and serving a tariff.

She said: “People would go into prison and unsurprisingly they would acquire a mental health condition, because the criminal justice system is an absolute mess.

“They are limited in social contact and don’t always have access to physical exercise. There isn’t enough fresh air, lighting and the right environment that would support their mental health.”

Black men are far more likely than others to be diagnosed with severe mental health problems, they are also more likely to be sectioned under the Mental Health Act.

However, research has indicated that up until the age of 11, Black boys do not display poorer mental health than other boys of the same age.

Turner believes that conclusions can be drawn from these findings.

She said: “Societal or environmental pressures, expectations based on opportunities or socio-economic and urban considerations, start to have an impact on mental health.”

Mind in Croydon run a peer support outreach programme, where they employ people who have lived experience, to go back into the acute psychiatric wards and offer support on pre-discharge from the hospital.

Many of those people who are offered support tend to be young Black men, mainly from Afro-Caribbean backgrounds.

Turner explained that people often get trapped into the cycle of the mental health system, sometimes referred to as the ‘revolving door’.

This will see them go into hospital, have a period of treatment and assessment, then discharged back into the community without adequate support which can lead to them becoming unwell again and returning to hospital.

Turner noted that in her experience it can be very quick for people to assume that a young Black man is becoming very mentally unwell with schizophrenia.

She explained: “This could date hundreds of years, but the medical profession is predominantly a White patriarchy, and the symptoms are medicalised based on what their perception of behaviour should be.

“For example, how we talk to each other, the volume in which we talk to one another, how polite society is perceived, and I have seen this on display on the wards and in the prisons.”

Turner witnessed young men being told they were becoming ‘aggressive’ when they were having their liberties detained and felt that no one was listening to them.

They would increase the volume of their voice to express that frustration, only to be told that they were becoming mentally unwell.

In these circumstances often the course of action would be to restrain that individual and administer restraining drugs.

They would then be placed into a segregation room, or in the case of prisons, restrained and put into cells.

Benefits of talking therapy

One form of treatment for mental health which is becoming more popular amongst Black men is talking therapy.

This is largely due to the outreach work of various community and charity led campaigns to raise awareness within the Black community.

Dr Stuart Lawrence, Educator, Author, and Consultant, has spoken very openly about his struggles with his mental health for over 30 years, following the racist murder of his older brother Stephen, in Eltham London on 22 April 1993.

He said: “Therapy is real, mental health and mental awareness of oneself is real.

“I’ve been through dark days. I will be in counselling forever.

“The defining moment of my childhood obviously was losing Stephen, but I had many difficult moments before then.

“I honestly thought my life would be nothing major, just someone that plods along.

“In honour of my brother, I try to keep his legacy alive every single day.”

DR STUART LAWRENCE – Photo Credit: Cheryl Fergus-Ferrell

He stressed the importance of men having a safe space where they can engage with each other and unload their problems, such as barbershops, pubs and social clubs.

He said: “We don’t always have those spaces. Where are those spaces that are safe spaces to do that unpacking?

“I’ve got a group of friends that I have known for 40 years, that’s my safe space.”

Speaking about the importance of youth clubs, Lawrence said: “I cut my teeth in my craft of being an educator and a youth leader through my own experience of youth clubs.

“I only replicated what they did to me and to others.”

The National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health published the Ethnic Inequalities in Improving Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT) report in 2023.

Key findings from the report highlighted that, in comparison with White British people, people from minoritized ethnic groups (excluding Chinese people):

- Experienced worse outcomes, although this has narrowed in recent years.

- Waited longer to be assessed.

- Were less likely to receive a course of treatment following an assessment.

The report also found that inequalities in mental health outcomes for people from minority ethnic groups are associated with:

- Increased symptom severity at the initial assessment.

- Living in areas of higher deprivation and higher unemployment.

- Waiting longer to be assessed and treated.

Recommendations focused heavily on Integrated Care Boards (ICB) and those in leadership roles, responding to the inequalities highlighted in the report.

It stated the need for practical training to improve their understanding of mental health inequalities and to adjust their approach while engaging with ethnic minority communities.

For more information about the services offered by Mind in Croydon visit www.mindincroydon.org.uk or call 020 8668 2210

Croydon BME Forum run workshops focused on mental health www.cbmeforum.org or call 020 8684 3719

Featured image credit: Rawpixel via iStock

Join the discussion